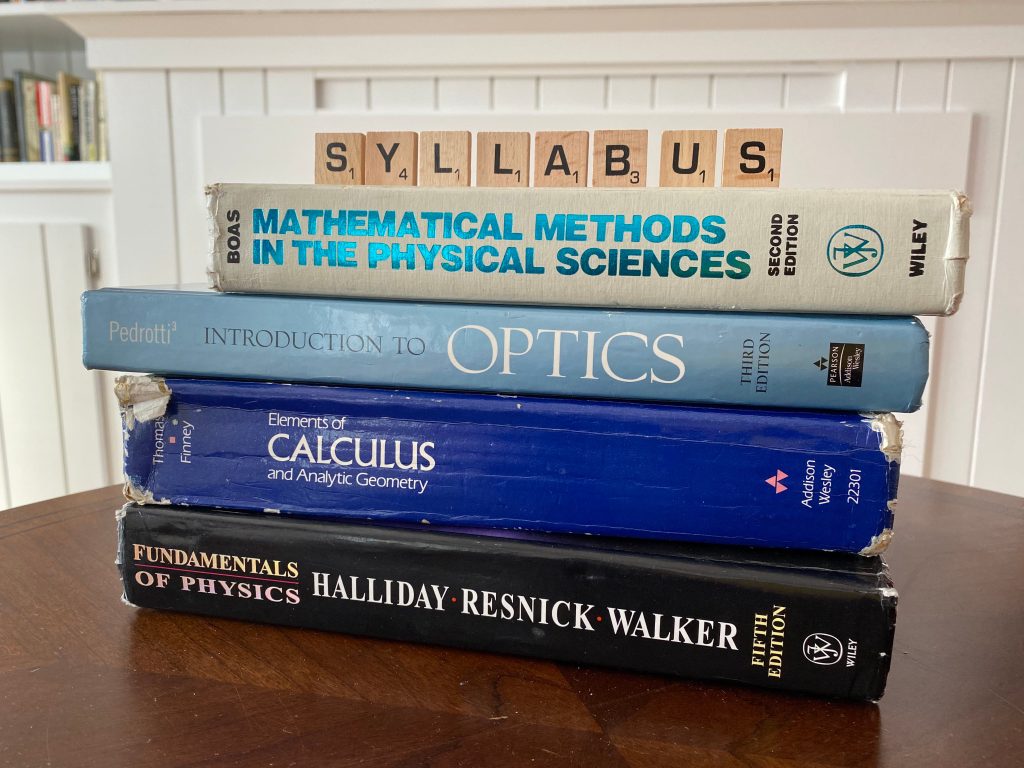

Syllabus

Getting back to classes soon, and people are updating and crafting syllabuses. I recently sent some extra information to the department about syllabus best practices. I definitely have prior posts on how to think about your syllabus. Specifically, your syllabus is your contract with the students! And, that you can use your syllabus to help set expectations!Here are a couple new considerations on the topic that I hope are helpful. Comments are welcome!

Give as much information as you can. You cannot over-communicate in your syllabus. I know this can make them long, but again, if it is your contract and a way to convey your goals, expectations, and ideals for the class, what is the risk of saying it clearly? What is the risk of not saying it clearly?

Have a clear grade scheme. I only started doing this a few years ago, when I realized that I wasn’t, and I was asking the students for a lot of trust by not communicating my typical standards for assigning letter grades. Since our society has trust-issues with women, I figured I better be clearer. It is a matter of transparency of to tell your students how many points they would need to get an A, B, or C.

I have heard all the usual justifications for trying to keep students in the dark: “I am nice, and I want to help them by adjusting the cut-offs,” or, “I just don’t know until the end where these cut-offs will be.” But I think that is unfair to students. The good news is that you CAN do change the cut-offs and shift them lower when assigning the grades – you just can’t shift them higher. Making these changes doesn’t preclude you from telling them what your typically do up front. You can always make the grade scale more lenient (not more strict), but it is important to communicate clearly to the students what the expectations are to begin with for getting an A, B, and C.

Inclusion, Equality, and Dignity Statement. We added a section on Equity, Inclusion, and Diversity recently when our campus was hit some gone racism graffiti, and the students rightly pointed out we were not doing enough. One of the graffiti writings was found in a bathroom stall in our building, and we didn’t realize it was there. We have created mechanisms for reporting about the climate, facilities, and community interactions. To communicate that to our classes, we encourage the following syllabus language:

Everyone in this class is an equally-valued member of this university and our community. We expect you to treat your classmates as honored colleagues in the collective endeavor we are all involved in: to understand the natural world and use that understanding to improve our society.

In particular, bias against or denigration of anyone in our class because of their gender or how they express it, their sexual orientation, their religion, their national origin, their race or ethnicity, or a disability they may have will not be tolerated. If you are the target of this sort of bias or if you witness it, please report it directly to me and I will take swift action. If you don’t feel comfortable talking to me, you may report it anonymously to the Physics Department at this link.

The Value of Failure. A lot of learning in science is through trial and error. Error is the same as failure, and it is a vital feature of learning, yet students don’t like it. It is uncomfortable and scary. They are often not used to it, if they are typically high achieving. I have a very long section of my personal syllabus devoted to expectations for the class, and these concepts play prominently. I paste in my words below, in case you want to use any or all of it.

Living Document. As things adjust and change, you can update your syllabus. Indeed, you should and you should continually notify the students in your class about these updates. I recommend posting updated versions to your online communication and course management software (Blackboard or similar) with a note to say that the new version supersedes the previous one. The best practice for transparency would be to keep up all the different versions to be accessed by the students.

Boilerplate Language: Every university has boilerplate on a variety of topics from cheating, excused absences, or other things. These really need to be in the syllabus for completeness. Again, it’s a contract – people need to know what they are agreeing to.

What do you think? Comment or post.

Expectations. Below is a quote from my recent syllabus on expections including language on the value and need for failure and learning from mistakes in science. Hope these help.

EXPECTATIONS: I expect that you are committed to doing the work to understand the material of this course. I also expect that the level of work each person needs to commit for each part will vary from person-to-person and from topic-to-topic. The role of the instructors (Jenny and the TA) is to act as your coaches to guide you in your learning. Ultimately, the learning process belongs to you alone. Consider your learning much like how you would learn a new physical skill, such as shooting hoops, playing an instrument, or a new dance move. You should practice on your own and you can self-assess your progress. I will help you, but I cannot do it for you, just as Simone Biles’s gymnastics coach does not jump on the beam to show her how it is done – I cannot really show you how to do these things. You just have to try, fail, and try again.

Some students find this type of teaching annoying because they want to lean back and let the professor drone on in lecture classes. These students often think that I am not working because they are doing all the work. This is simply not true. Instead of lecturing to all, but missing learning moments for most, I am coaching you each one-on-one to make you all stronger. I may challenge you differently in order to bring you each individualized instruction. The other reason why I know this type of teaching is more work for me (not less, as it might seem) is because many professors also find this type of teaching difficult. It is far easier to write lectures and deliver them to sleeping students than to have to think on your feet and answer questions on the fly to help you.

Practice. In order to become an expert at something, you need to practice for 10,000 hours. In any Physics class, we typically expect 10 hours of work per week on each class. Depending on your level coming into this class you may not need to spend 10 hours per week on this class, or you may need to spend more. The class is 13 weeks long, so that is approximately 130-150 hours per class. By the time you complete the physics major, you will have taken 8-10 lecture classes. The minimum Physics major doesn’t make you an expert in physics, but doing a Ph.D. will give you those expert hours (5-6 years working 40-60 hours per week). You can estimate all these hours and see for yourself. Regardless, in order to learn, master, and ultimately become and expert, you need to practice. The goal of the homework, in class work, and other problems is to give you the practice you need to master the work. That is a major benefit of the Active Learning Style.

Failure. There is no problem with trying and failing, as long as you learn something. In fact, in science, your goal is often to test a model, theory, or hypothesis and try to get it to FAIL. When it fails, and how it fails, teaches us something. Thus, as scientists, we strive for failure. We do not work to “prove” anything. That is a one-way ticket to false truths, we work to disprove models, theories, ideas. Trying to prove theories leads to results that are not reproducible and falsifying data. These do not help science move forward. We learn far more from good, solid, scientifically reliable failure than we do from FAKE proof. For instance, in physics, Newtonian mechanics works for many problems, but not all. Instead we need relativity. Without relativity, we cannot have satellites or other communications that move at the speed of light. In fact, Newton got it wrong – he failed, but his failure still works in many cases and is still taught today. Some people get caught up in failure, success, grades, being a hero, but in science, there is really no such thing. So, be brave, try your best, failing is just nature’s way of telling us what is real and true.

Cumulative nature of science, learning, teaching. If you notice, all the exams are cumulative. This means that they cover all the materials up to that point in the class. So, exam 1 covers the materials in homework 1-4, exam 2 covers the materials in homework 1-8, exam 3 covers 1-11, and the final covers everything, too. Physics, and science in general, is cumulative. We cannot separate what we learn in the second half from what we learn in the first half any more than you would be able to do that for a foreign language.

In fact, the way we structure our entire physics major curriculum (all the classes you take) is set up to build one on top of the other. When you learn quantum mechanics, they will assume you understand and remember what you learned in this course! The concepts carry forward, and you learn them deeper, with new mathematical tools, and it reinforces the concepts and skills you learned from previous courses. Our curriculum is iterative, much like real science, so you will also see several topics several times in new contexts and with new jargon and concepts attached. Keeping in mind the big picture as well as the local activities you are doing in your current class will help you to understand why we do things the way we do.

Of course, we can always improve our teaching and curriculum in the department, so if you can think of something that would make this class or the physics major better, please don’t hesitate to let me know. I am the department associate chair. I am also on the undergraduate climate committee. You can also talk to Prof. Jack Laiho (lead academic advisor) and Prof. Eric Schiff (the department chair). Getting to know the leadership in the department is a good way to affect change for yourself and your peers for years to come.

Science and being a scientist. Finally, many of the questions and hands-on work both in class and the laboratory are open-ended. I may not know all the answers. Being a scientist is not about knowing the answers… it is about knowing how to find the answers. As a card-carrying physicist, I have confidence that I know how to find the answers through direct trial and error experimentation. My job in this class is to teach you how to find the answers for yourselves. The answers may or may not be available on the internet. You will get the thrill of discovering how science works, if you follow the process and make the discoveries in class and in lab for yourselves (as a team).

Another stereotype of scientists is the “lone scientist.” Scientists do not work alone. They do not work in a vacuum (not even astronauts). They work with others in collaboration. You are in groups in this class and in lab because learning to collaborate is an essential element to learning and doing science. Even a theorist coming up with a new theory must talk to people, get the idea out there, and test the predictions with experimentalists.

One of my biggest pet peeves is how society doesn’t associate science with creativity. Part of the reason is in how we teach (standard) science classes. We often teach that there is a “right” and a “wrong” answer. For those of you who like this aspect of science (the ability to be right), I have good and bad news. The good news: your homework problems will still have a right answer. The bad news: cutting edge science, which is still under debate, may not. This is where a lot of scientific ingenuity and creativity comes into play.

Finally, people also think that you must be brilliant to be a physicist, but instead you must be smart. They are not the same thing. Smart people are observant, make conceptual connections, think creatively, and are hard working. You must practice your craft. Many seemingly “brilliant” people are actually very hardworking, acquiring knowledge through practice, failure, and retrying, in order to appear brilliant when the occasion arises. I encourage you to work on these skills: hard work, creativity, observing, making connections, thinking conceptually. These are skills, and they can always be improved with practice, and they can be applied broadly.

I am really excited about teaching you in this course. I endeavor to do things in the class to help you struggle well, so that you learn. It is the most important part to me – that you learn. I am here to coach you. Also, I am admittedly human, so if I make a mistake, please let me know (with kindness). I am looking forward to working with you all!

Recent Comments